“I think sometimes when you’re the quiet person in the room, you become a lot more observant,” she shares.

Based between Johannesburg and Capetown, Andy Mkosi’s first exposure to photography was through family photo albums. Eventually, she bought her first camera and continued the tradition of photographing her family.

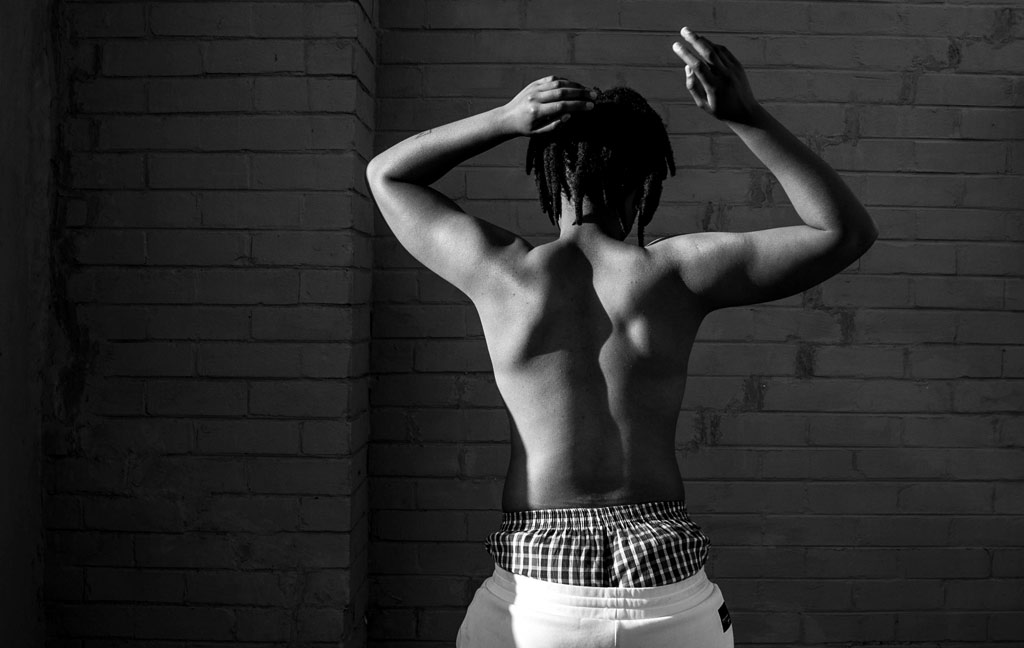

When asked why she focuses on black and white photography, Mkosi shares, “I think it’s a technical thing, more than anything else.”

Today, however, she discovers that black and white is more than just a byproduct of technical concerns. It has become her style.

Photographer and Create Fund winner Andy Mkosi shares why.

Shutterstock: I love your photography style! So, I guess I’ll just jump right in. What is it that you love about documenting?

Andy Mkosi: I think sometimes, when you’re the quiet person in the room, you become a lot more observant. I’m just curious about the world that I live in and exist in.

There are moments that we can’t relive, and I think that’s where documentation becomes very important.

We just came out of an election period and, although I didn’t document enough, I knew that when I went to the polls, I wanted to document that moment because it’s such an important moment in our country, where democracy is slightly changing.

License these images via Mkosi Omkhulu x2 x3 x4 x5 x6.

SSTK: How did your relationship with photography start, and why did you stick with it?

Mkosi: My first interaction with photography was after high school. This was when I picked up a camera. Before that, I was consuming images through family albums.

As to why I stuck with it, *laughs* I do not know why this is funny but I think it’s because I just enjoy documenting. I am really great at it too!

So, doing something I love that contributes to my livelihood is great for me.

SSTK: What’s one thing you will never get tired of documenting?

Mkosi: Just life on the fly, like fly-on-the-wall type of things. It started with hanging out with my family, and then I’d see these moments that no one else notice.

So, I think I’ll never ever get tired of like documenting my family. Being able to add to that existing archive of photographs.

License these images via Mkosi Omkhulu x2 x3.

SSTK: For sure. You do a lot of black and white photography. Let’s talk about that. How did you end up with this style?

Mkosi: In the beginning, I didn’t really know what I was doing. I knew of photography and photographs but I didn’t know anything about a camera.

So, when I first bought one, I didn’t necessarily ask for advice on which camera to purchase. I just bought what I could afford at the time.

What I found was that every time I made images, I didn’t enjoy the ones that I made in color.

I think it’s a technical thing more than anything else, where you’re like, “Okay, cool, I need to cheat this thing because my camera can’t capture with much impact when I do it in color,” and I was struggling.

But once I switched it to black and white, something happened. I don’t know what it was, but when I look back at the images, there’s something there—I don’t know what—but it became my style.

When it came to creating timeless images, black and white became my go-to.

SSTK: I think that’s such a great way of approaching things—the act of allowing what’s lacking to expand your creativity instead of like, limit you.

Mkosi: Exactly! Yeah.

SSTK: You mentioned timelessness. What do you think makes a black and white image timeless?

Mkosi: Sometimes, you can’t tell if the image was made in the morning or nighttime. It’s more about, “What is happening here?” You know?

If you have the right frame, it encourages people to concentrate on the subject matter than when it was made. They’ll gravitate toward the piece of imagery. What is that image saying to me? Why was it made?

You deal with the subject matter and the narrative more than the context of the time and all of these other factors that go into making an image an image.

SSTK: When we strip the colors off of these images, how do you think that affects the image itself? How do you think that affects how people view it?

Mkosi: It then becomes more. It’s not just about the beauty anymore, but again, about the subject matter.

I appreciate color photography. I have nothing against it. But I think with black and white, it removes all the fluff and it’s just the subject matter that becomes the intrigue.

And I may stand corrected, but I think if you look back, a lot of images that people share are black and white images because of the subject matter that they hold—be it about people fighting for their democracy or just someone documenting a time in their life.

License these images via Mkosi Omkhulu x2.

SSTK: Do you think that when a photo is in grayscale, sometimes it becomes more powerful?

Mkosi: To some degree, yes. It’s the removal of all the other stuff, you know? It’s like, look at what’s happening in the image more than what the person is wearing or what’s happening in the background. You really are able to quiet everything and zone into that one thing.

For me, this particularly became vivid and clear when I started making images in clubs. I wanted to photograph people within the LGBTQI+ spectrum in a way that is not demeaning of who they are . . . in a way that makes classical images. I wanted to find moments.

It eventually became a project called Mid Groove. It’s like finding moments in the midst of a party or a club space or whatever.

Finding moments that are quiet in this loud place. Moments where there is affection. Moments that people don’t really pay attention to.

License these images via Mkosi Omkhulu x2 x3 x4 x5.

SSTK: I love that! In the email, you mentioned that we haven’t reached full representation in the stock photography industry yet. It’s already 2024, why do you think that is?

Mkosi: That’s a good one. I think that maybe businesses and society should also take the initiative to say, “Okay, cool, when we take on client briefs, I want this type of model, or I want to shoot in this type of area, or I want to tell this story through this narrative,” you know.

It’s like expecting politicians to fix all our problems—I don’t think it works like that. It’s a hand-in-hand thing.

But it’s important that structures like Shutterstock create funds like The Create Fund, no pun intended, in order to better diversify the pool.

At the end of the day, no one is going to save us if we don’t save ourselves. It’s a matter of developing more platforms or leaders in the stock photography space who are of oriental descent, who are Brown people, Black people, queer people.

We need to represent those corners that we all come from.

SSTK: I think I’d like to end this with a classic: How important do you think visual storytelling is in today’s era when everybody can easily take photos?

Mkosi: We all can see, but we don’t see in the same way. It’s really about being intentional about what it is that we’re doing with our cameras.

With photography, a lot of what we do is based on experience. No one can take your personal experience away from you. No one can take mine.

Those experiences add to what output we have as visual storytellers.

License this cover image via Mkosi Omkhulu.

Recently viewed

Source: shutterstock.com